Trip Overview

This is the story of a solo canoe trip into the Barren Lands of Northern Canada that I did in the summer of 2024.

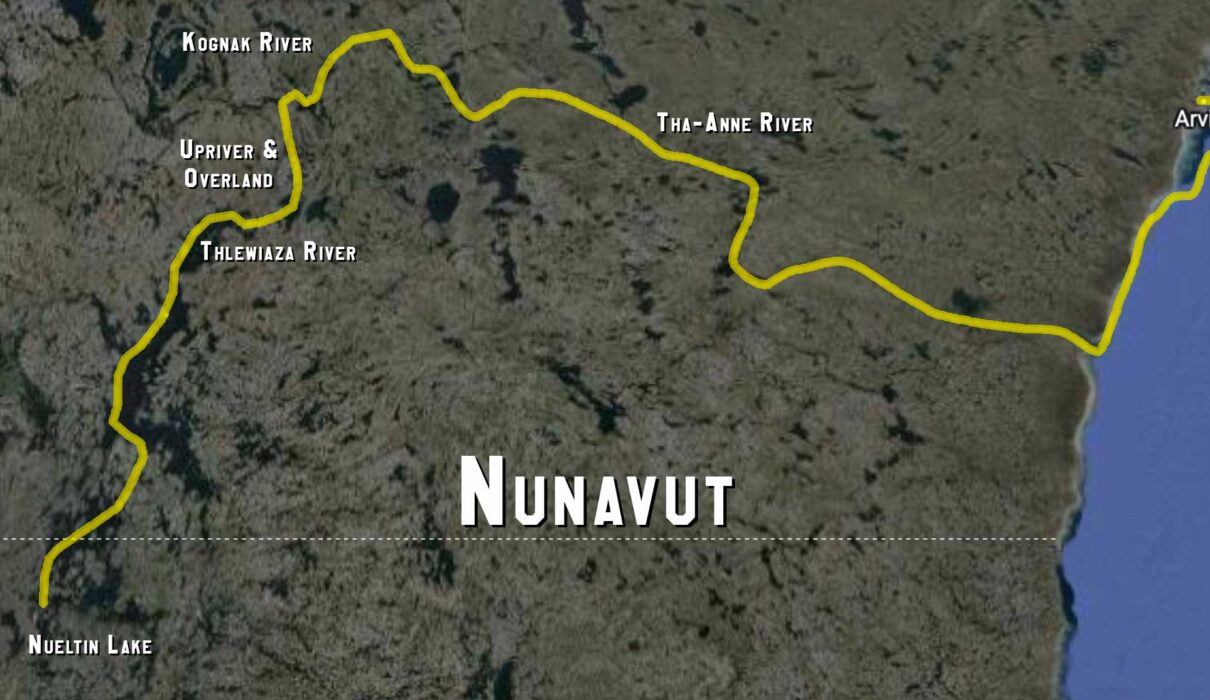

The goal was to traverse Nueltin Lake, ascend the Kognak River, cross the height of land and then descend the Kognak to the Tha-anne and thence down to Hudson Bay. That’s NOT how things ended up turning out and I had to make some pretty major modifications.

First, here’s a video breakdown of the trip I had planned…

The plan was that as soon as the ice on the big lakes melted I’d fly into Nueltin Lake, a giant body of water which straddles both the Manitoba-Nunavut border and the treeline. Once north of that line trees become stunted little shrubs and grow only in the most protected areas.

Once at the top end of Nueltin Lake I planned to descend the Thlewiaza River down to Sealhole Lake, then turn North and proceed up a tiny creek, across very small lakes, and then over the height of land until I reach the Kognak River.

The Kognak runs generally East until it becomes part of the Tha-Anne River which flows down into Hudson Bay and the land of polar bears. From there I’ll make my way to the small native village of Arviat to end the trip. I’m guessing this whole trip might take 4 to 5 weeks if the water and weather conditions hold up.

Trip Preparation

To give you an idea of the preparation, here are the contents of my expedition medical kit…

Here’s how I make the “energy balls” that’ll keep me going, mile after mile…

And here’s the pile of food I took with me.

This is what a pile of 133,472 calories looks like. I often doubt whether l’m taking the right amount of food on a trip so l double check the amounts with math. I first create a spreadsheet and enter every meal and every snack along with its caloric value (1 gram of dry protein or carbohydrate is 4 calories, 1 gram of fat is 8.) If I manage to pull this trip off in 30 days that means l’ll get about 4,500 calories a day; enough to push through and only lose about 10 pounds. if the trip goes longer than that, well, I’ll either lose more than 10 pounds or do some fishing, snare a lemming, or shoot a goose.

Trip Video

It’s always difficult to get footage in the field, especially when you’re travelling alone and have to do absolutely everything yourself. That being said, I did more videography on this trip than ever before, and produced a 2 hour documentary which I published on the Essential Wilderness YouTube channel.

Getting to the Starting Line (i.e. The Adventure Before the Adventure)

To get to the starting line of this Arctic tript took 30 hours of driving and a 2 hour bush plane flight.

On the first day of the drive I crossed British Columbia and entered Alberta. I passed through the town of Hope where they filmed the first Rambo movie and Sylvester Stallone is regarded as a demigod. I passed through the Rocky Mountains, drinking in the splendor of Yoho and Banff. And I took advantage of the long drive to catch up with old friends on long phone calls.

There are a lot of known unknowns on this trip. I know that I don’t yet have a confirmed bush plane flight; I was told that it would probably be available on the day I needed, but there are no guarantees in the north. I don’t know if the water levels will be sufficient to traverse between watersheds, this being a year of extreme drought in the North and the West. And I don’t know if the lake I need to traverse is ice free yet and – if it’s still frozen – whether the alternate routes are traversable.

In the end I’ve made as many contingency plans as I can think of, and I trust in my skills and mindset, so at this point, I just have to roll the dice and go.

On the second day of driving I crossed the gently rolling terrain between Calgary and Saskatoon. The prairies have their own particular beauty, and I find driving through them on the smaller roads and highways very hypnotic. One more day of driving and I should reach Thompson, Manitoba, the gateway to the north. I can’t wait to get back to the harsh granitic beauty of the Canadian Shield.

On the third day of getting to the starting line I drove from Saskatoon to Thompson Manitoba today, passing through Melfort, Nipawain and The Pas on the way. If everything works out then tomorrow I take a 4 1/2 taxi r to the float plane base and a 2 hour flight into the North to the edge of the trees to start the trip into the Barrens.

It was incredibly sad to pass the site and memorial of the 2018 Humboldt Broncos crash where 16 people – mostly kids in their late teens – were killed. I feel for the injured survivors and the families of the dead.

Day 1, June 24

After a four hour and $765 taxi ride, I am finally at the float plane base in Lynn Lake, the literal end of the road in Northern Manitoba. From here it’s a 2 hour flight north across The Land of Little Sticks. Excited!

There is so much water up here it is unbelievable. Everywhere you look is a lake, a pond, or a bog. From studying the satellite photos the last 4 weeks there has been a giant bank of cloud sitting above this area and I guess it’s been raining continuously. Even from up here, I can see that many of the Shoreline bushes are underwater – I have been worried about not having enough water, and now there may be too much. At least, if the floatplane engine gives out, then we’ll have no problem finding a place to do an emergency landing.

After a very bumpy two hour flight against the continuous headwind, we are here! Not only is this a Beaver, a now discontinued plane that was the workhorse of the North for the longest time, this is the 38th Beaver ever built according to the serial number. Despite being about 60 years old, it has been repaired, strengthened and rebuilt so many times that it’s still in the air (I’m talking about the plane, not me!)

Brad the pilot used so much fuel that he now needs to add extra just to get home. Fortunately, he took a bunch of Jerry cans in the pontoons of the plane (where I also had to store my bear spray because we didn’t want THAT) going off in the cabin. He took off for home, leaving me at 59.7° latitude north, just one or two days paddle from the Nunavut border if the weather is fair.

Well that wasn’t in the plans! At the very southern tip of Nueltin Lake is a lodge that has been abandoned for years. A few years ago it was bought by a new owner, who is now working to restore it to its former glory with equipment and supplies flown up from the South. Nick, Steve, John and Uli were up for a week building a new dock for the float base. They offered to feed me, an offer which is difficult to refuse. So I traded a few hours of helping with the dock for cheeseburger and fries, the last meal I expected to have on this remote lake. They invited me to stay for a few extra days, but the tundra is calling. This hospitality is actually the norm up here, not the exception. You take care of other people because you never know how they’re going to take care of you.

Day 2, June 25

The boat is packed, the spray deck is attached, and I am ready to go! 150 kilometers of Nueltin Lake await before I reach the first stretch of moving water.

In the last 30 days Nueltin Lake has gone from being at a historically low level to being much, much higher than normal. Heavy rains in the South have swelled every creek and waterfall flowing into the lake, and raising it more than 6 feet in the last month. This might make the rapids of I have to traverse to get to Hudson Bay very, very challenging.

The going was slow today. Partially the boat is still very heavy because of all the food supplies. Partially this is just a slow boat, the skin over frame construction is convenient, but it is not as fast as my hard shell boats. Finally, I’m not yet in paddling shape; you can, and should do physical preparation for stuff like this, but ultimately nothing prepares you for hours and hours of paddling, except for hours and hours of paddling. By the end of the day, I was limping along and had to take frequent breaks; I expect this will improve over the next week if I just get enough calories into me and get some good sleep.

Day 3, June 26

Got up early and started to make good progress, but after about 10 km, I heard a thunderclap in the distance. Soon these giant clouds were all around me, the wind became extremely gusty, and it was time to get off the water and stop being the tallest object on the giant lake. This is why I try to stick close to shore.

I pulled onto a small island waiting for the cold front, and the thunderstorms it ,to pass. In between bands of rain I tore through the only physical book I have with me; The Three Body Problem by Cixin Liu. This was the best science-fiction I have read since Verner Vinge; it’s really too bad that space and weight constraints prevent me from bringing more books, especially on a trip where periodically being windbound is just a fact of life. Amazingly the bugs aren’t too bad; I’m sure this will change as the season progresses and I work my way North.

Man makes plans, and God laughs. The rain, lightning, and heavy wind didn’t relent, so now, on a lake full of gorgeous campsites, I’ve got the most marginal tent set up I’ve had to use in a while. It was the only spot wide enough and long enough for my tent, but now I’m sleeping on a slope where I’m going to slide foot first towards the water all night. I also think I’m on a game trail so I took extra care setting up the bear alarm tonight. I’m going to try and sleep by 9 pm, get up early, and hope for early-morning calm to allow safe passage to the shore of the lake where I can be sheltered from winds from the west. Plus, there are a lot of sand beaches on that shore, so if I get windbound again at least it will be in a prettier place.

Day 4 June 27

To beat the wind I got up at 4:30 AM and was on the water by 530.

Unfortunately the wind got up about the same time as me, and soon I was battling heavy gusts and waves. I barely made it 5 km before I had to stop, but at least I improved my campsite. I set up my tent so I can nap and wait for conditions to improve. On the plus side, my campsite is on top of an esker, which is a very pretty place with lots of sand and open vegetation. Lots of animal tracks, too, one of which I got to run into later in the day…

So far this trip is proceeding at a dismally slow pace. This lake is 150 km long, I’ve only been managing about 10 km a day due to wind, but there is a whole lot of expedition left after that, so spending 15 days getting to the top of this lake isn’t going to work because I’ll still have another 700 km of unknown country left. I’m hoping for a break in the weather to put some miles behind me, but if things stay this windy, I don’t know what I’m going to do.

BEAR! And a large one too. I keep my campsites and my kitchens, separate to avoid contaminating my gear with a smell of food, so I was heading to the kitchen with my stove and dinner (hoping to eat early so that I can paddle later in the evening if the wind drops) and there I saw him; a great, big, beautiful, black bear. He was minding his own business, shambling across the landscape, nose down, looking for food. I relaxed and took photos. Then he turned towards and started heading my way.

When he was about 200 feet away I chambered a 3” shell of 00 buckshot and fired it into the air. The bear startled and came to a halt. I chambered another shell, but rather than waste ammunition, I started bellowing in a weird deep yodel. He had had enough of this crazy person, turned around, and galloped away.

I kept the bear spray, and the shotgun close hand for the rest of the day, but I am looking to relocating to an area with less bear tracks, bear turd, and bears.

This is the third time on a canoe trip that I’ve used a shotgun as a noise maker to scare away bears; it has worked twice, including today. I’m glad I saw him, and I’m very glad it ended peacefully.

After being trapped on shore most of the day, the wind started subsiding at about 8 PM. By 8:30 PM I was on the water paddling north. For once it was easy to make progress, even an easy stroke ate up the miles.

I hadn’t gone very far when I saw a large yellow-brown animal shambling on the shore. it would disappear into the bushes and then re-emerge. At first I thought it was yet another bear, likely a grizzly this time given the coloration, but then I realized that my sense of scale was completely wrong. It was a giant porcupine, the size of a medium dog. When I went in close, he scampered up a tree and chattered his teeth at me; I stayed long enough to get a photo, but then decided I had stressed him out enough and went on my way into the evening.

By midnight I was still going strong, and given the fact that the never really dark up here this close to solstice there was a strong temptation to paddle through the night. Ultimately it was a difficulties of navigation by twilight that drove me to shore. I made a camp on top of a steep esker with a stunning view, and set both my tripwire bear alarm and my motion alarm.

Day 5, June 28

Back on the water, making miles when I can. We are officially north of 60° latitude, putting us into the territory of Nunavut, previously part of the northwest territories. It’s amazing how the tree line coincides with this political boundary here; the tops of most of the islands are tundra, surrounded with a fringe of trees at the base like a tonsured monk

Today was a very hard day. I was on the water from 9 AM to 7 PM pushing 275 pounds of boat and gear, plus the weight of my own body, against an unrelenting North wind. Despite using every trick I know, progress was so slow; 10 hours of work only brought me 17.5 km of the bird flies from where I started today (although, admittedly, it’s probably more like 25 km as the fish swims).

Unfortunately, I got news today by satellite text that the weather tomorrow will be very, very windy with extreme gusts. If this is the case, then I’ll be windbound here on my tiny tundra island; fortunately the tent is pitched just downwind of a thick wall of dwarf black spruce which should lessen the force of the gale. Let’s hope that the weather forecast is wrong!

Day 6, June 29

This may look like an idyllic beach, but I guarantee you getting to this beach was anything but idyllic. The wind is proving an incredible obstacle on Nueltin Lake, and the large size of the lake means that the waves can get pretty big after the wind has been zooming across the surface of the water for a couple of miles. I respect bears, but the real hazard up here are the large lakes and the cold water.

I had a necessary one and half kilometer crossing this morning, and without wind, I could’ve done it about 15 to 20 minutes. Instead it took an hour battling the wind, on red alert for breaking waves or developing thunderstorms the whole time. The wind was so strong that It blew me 1 km sideways, despite my best efforts to go on a straight line. When I finally slid into this protected bay, I was so relieved. A little while later it was out back into the wind.

I was out in the big swell, trying to stop my canoe from turning sideways in the waves when I spotted this newly built cabin at the foot of an esker. It didn’t look like anyone was home.

The wind forecast for the rest of the day, and for tomorrow is pretty dismal – high winds all the time from varying directions. I found myself thinking, “Cabins in the North are usually unlocked, and wouldn’t that be a nicer place to wait out the wind than some bug infested campsite?”

I actually swung the canoe around and started making my way there when I started having second thoughts about the change of plan. It was only 4 o’clock, and I’m so far behind schedule because of the wind that every kilometer counts. Even if I only went a little bit further today then that would be a little bit of distance I wouldn’t need to do tomorrow. It was a real slog, but in the end I covered another 7 or 8 km before packing it in. My body is so sore from all the full force paddling today and yesterday.

I’m finally in the so-called “Narrows” of Nueltin Lake, a complex maze of islands and channels that separates the southern from the northern portion of the lake. There was even a little bit of current flowing north, which allowed me to rest for a couple of minutes, the water moving me against the ever-present headwind. This is, by far, the most complicated lake I have ever been on. Your navigation skills had better be on point up here…

Day 7, June 30th

I came across an abandoned fishing camp; it had six or seven buildings, and each one of them had been ransacked by bears. I will never understand why bears find foam mattresses so delicious, or why they feel compelled to sink one of their canine teeth into every can of mosquito spray they find. It is sad to see this once great chain of lodges that introduced so many people to the north falling into disrepair and being reclaimed by the wildlife and landscape, and I hope that the new owner is able to restore at least some of them to glory. On the other hand, it does mean that I have this gigantic lake entirely to myself so far.

I had long been worried about great sheets of ice, blocking my progress on the northern part of this lake; Nueltin is notorious for keeping its ice well into July. Well I passed through the narrows and into the northern portion today, and the only ice I could see is up at the shore. Still a bit strange to see this much ice at the height of summer…

The trees are getting much scarcer now, and the landscape is mostly covered by varying types of tundra. It’s a beautiful kind of bleakness. My tent is pitched on top of a dense dwarf cranberry tundra; the berries of these plants are unique because they actually become sweet the year after they appear on the plant. The delicious, sweet berries. I am eating now grew last year, then sat underneath a thick blanket of snow for the entire winter.

Day 8, July 1st

What are we going to eat for breakfast today? The same thing we do every morning, 2 cups of dry power oatmeal reconstituted with lakewater. The only difference was that today I added a bunch of the delicious year-old ice-ripened cranberries. It was a good thing. I had a hearty breakfast because it was going to be a tough day…

Ice! Yes, it’s July, and yes, this is a freshwater lake, but I came across my first ice floe today. It was what you call ‘black ice’, ice that is in the process of melting that can be pushed aside or broken through with lots of freshwater leads.

Picking my way through this was a fun puzzle initially, and I got to the other side thinking that I was home free; the fabled summer ice of Nueltin Lake had been surmounted. Hah! The lake had other ideas…

Feeling smug I continued on, and soon came across a vast sheet of ice. This was not only the crumbling black ice, but also large areas of much thicker and more durable white ice. This was a much more serious problem because it blocked the entire middle of the lake.

It was strange how the ice sheet creaked, cracked, groaned, and made splintering noises. I had read about this in the annals of polar explorers, but it’s quite a different thing to hear it for yourself. It also reminds you that this ice is mobile, and just because there’s a lead through it one minute doesn’t mean it’ll be there the next next.

Lakes melt from the periphery inward, so in theory, there is usually a band of ice-free water along the shore. I started making my way along shore, which was slow going and required, occasional ice bashing, but there are two major problems with this approach…

First, the shoreline of this lake is so involuted with peninsulas and bays, that if you follow the shore, it’ll take you 5 miles of paddling to make 1 mile of progress.

Secondly, the force of the wind acting on the hundreds of millions of square feet of ice means that the ice pack drifts from shore to shore like a slow motion air hockey puck. If the wind direction changes, even if it is super gentle, then it drives the ice up along shore, and you’re not going to go anywhere.

Icebound! I continued along the edge of the lake for hours, but was eventually stymied by a thick pack of ice going up to shore. The ice was too thick to push aside, but too crumbly to stand on, and drag the boat over. I was checkmated for the day, so I set up camp.

Getting around this is going to take portaging, waiting for the ice to melt, or the arrival of a strong wind to drive it all to the other shore. I’m too tired right now, I’ll figure this out tomorrow.

Day 9, July 2nd

When I woke up, I was elated to see that the wind had pushed the ice offshore by several hundred feet. This meant that there was no room to sneak around the point and continue going North without having to do an arduous portage.

I started breaking down camp, and then looked up again a few minutes later. The ice was coming back in and the open water lead was shrinking rapidly. Everything got thrown into the boat disorganized and I started paddling without my PFD, spray deck not attached, and my pot of muesli sitting on the bottom of the boat. by the time I made it through the 200 foot of open water had shrunk to about a 10 foot space. a few minutes more and I would not have made it.

It’s amazing how fast the ice comes in when a gentle wind gets the floes in motion. These two photos were taken in the exact same spot one minute apart, and you can see how high the ice has piled in that short time accompanied by the noise of 1,000 crystal chandeliers being dragged across the rocky lake bed.

This was such a beautiful set of Caribou Antlers, that I had to pull over. Think of how big this bull must’ve been! For the Dené and the Inuit – especially the inland Inuit – the Caribou were a source of food, clothing, shelter, and tools. it’s similar to how the Plains Indians relied on the Buffalo for all the same things.

Most of the day was dead calm, and now that the ice was a thing of the past I made good time and crossed several large bays. Towards the end of the day, though, I saw large cumulonimbus clouds move in from the west. These clouds, also known as thunderheads, are dangerous, because they produce lightning, but also because they produce strong winds, and even stronger sudden gusts. I had one last crossing to do but these clouds made me nervous.

I sat for a while, measuring the speed and direction of the clouds, and then, knowing my paddling speed, set off, like a madman for the far shore. They never caught me, although, ominously, the formerly warm air was now occasionally mixed with light gusts of cold air. A front was definitely coming in.

I made it over to the other side of the lake with lots of time to spare, arriving at Fox Narrows. I had heard there was a family of foxes denning here and so I went and looked for them. I found them, but not in the state I wanted to. A large area was covered with shards of white fur and ribs. Some animal, maybe a bear or maybe a wolverine, had absolutely massacred them. I hope that some of them got away and will be coming back to repopulate this gorgeous little pocket beach in the future.

The wind is very strong now, but I have used every guy line on the tent to hold it in place. And I took extra care in setting up my bear alarm tonight.

Day 10, July 3rd

No ice today other than some odd little patches of floating chunks in the lee of some islands, but lots of changing wind conditions. I have settled into a new pattern of paddling hard for about an hour, and then just collapsing for about 10 minutes to recover. I try to make sure I eat something at hourly intervals as well to keep the machine fueled.

I paddled for only nine hours today, picking a route through the dense sea of islands at the north end of Nueltin Lake. Every island is ringed by willow bushes, giant boulders, and a few krummholz spruce, and then is a dome of nothing but tundra and more giant boulders, giving it a very Weathertop feeling.

I was finally driven off the water by an intense rain and windstorm. That was OK because I had a lot of repair and maintenance to do tonight, including playing cobbler and fixing my portaging shoes, and playing seamstress and modifying my spray deck with a sewing awl and Frankenstein stitches. Being on an expedition means that you are always drying stuff and fixing stuff, usually both at the same time.

Day 11, July 4

Happy July 4th!! And a belated Canada Day; I forgot, because I was off doing Canadian things. And Happy Birthday to me; I am very grateful to my family for letting me go and struggle against the weather, the water, and self doubt here in the wilderness, the thing I want to do on my birthday.

Finally made it off of the big lake! The wind was fierce today and I had to work for every inch. In the rare, shallow sections, it was sometimes it was easier to use paddle as a pole and push on the lake bottom to move the boat forward than to paddle. Even now, in the evening, my lats and shoulders are still vibrating from the day-long effort.

There are three channels you can use to exit Nueltin Lake and descend to Seal Hole Lake. A moderately difficult northern channel, a very difficult southern channel, and a suicidal middle channel.

I chose the suicidal middle channel because the water levels are so high in both the lake, and the river that I was unsure as to the wisdom of running the northern channel. Accordingly, I went down the middle channel, knowing that I would portage around the waterfall that was in there. In general, the steeper the drop means the shorter the carry.

Nueltin, you’re a beautiful lake but with all the ice and headwinds, you don’t make it easy for people, do you?

I’m agonizing about a major decision tonight. Let me break it down for you and see what you would do…

I am now at Seal Hole Lake and could proceed one of two ways. I could either go slightly north and proceed to Hudson Bay via the Kognak and Tha-Anne rivers (plan A), or go slightly south, and get to Hudson Bay via the Thlewiaza (plan B). Both rivers go through the tundra, both rivers have a chance of seeing caribou, and both end up close to the same place.

Here are the challenges involved… First, I’m already significantly behind schedule. The ice and the wind on Nueltin Lake made for very slow progress to this point and I thought I would be here much faster. The Thlewiaza will probably be the shorter route – the other route has way more unknowns.

On the other hand, the Thlewiaza is running very high, close to historical maximum levels, will make the rapids much pushier. The water levels of the Kognak and Tha-Anne are unknown; although the two routes lie close together the one is primarily filled with water from the south, the other with water from the North.

Third, although my Pakboat Canoe is great, it’s not fast in the wind and the northern route has more lakes. It’s good in big waves but it really likes to stick to rocks in shallow rapids (which is dangerous, because it can lead to broaching). Based on very limited information, the Kognak may have lots of shallow rapids.

Fourth, I’ve been dreaming about the Kognak and Tha-Anne for years now.

The decision is killing me. Continuing with Plan A no matter the difficulties would be a point of pride, but the hero’s graveyard is full of tombstones reading “Plan A or Nothing.”

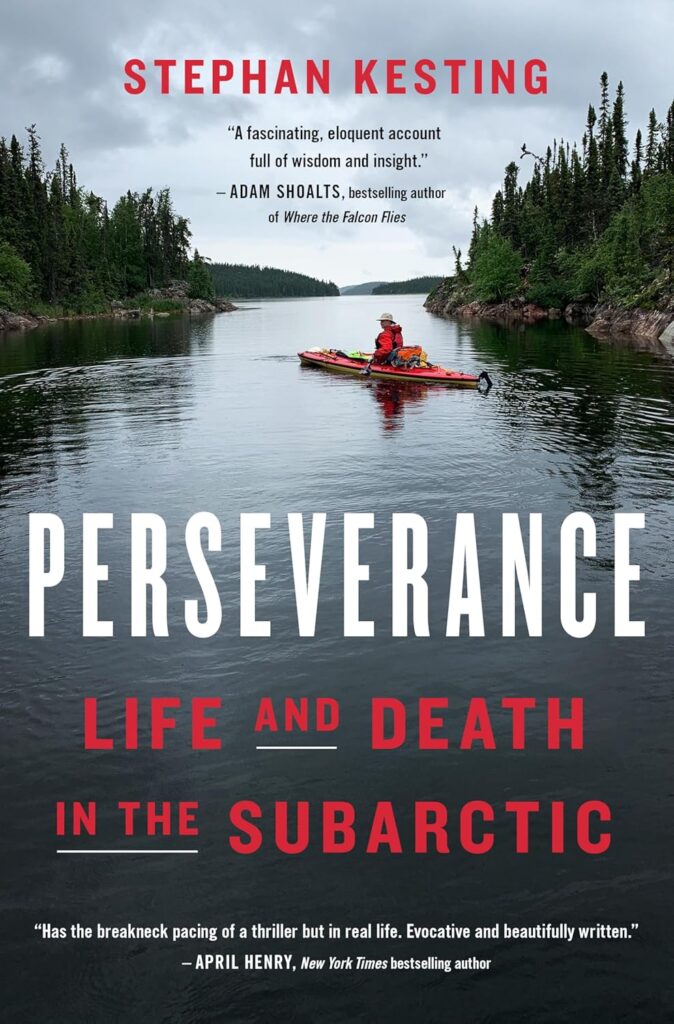

If you’re enjoying this story, please consider pre-ordering my book Perseverance, Life and Death in the Subarctic!

Day 12, July 5th

Well, I made a decision; I’m heading to Hudson Bay by an alternate route. It’s sad, but a sober self assessment clearly shows that’s my boat isn’t very well suited for the large lakes and small rivers on the other route. It does excel, however, in large waves, and since the Thlewiaza is in flood it has lots of large waves.

The only problem is I don’t have the detailed 1:50,000 topographic maps that I like to navigate with for this second route. I can use GPS in a pinch but mostly I’m trying to go and do this the old-fashioned way, by following the current and trying to not get lost when the river broadens out into small but very complex lakes. Every single time I’m in this country I wonder how the hell the first people through here figured out how to navigate this chaotic landscape, and now I’m going to get a little taste of that experience first hand.

Batten down the hatches! The winds were very strong today and they brought the occasional intense rainstorm and strong gusts, but at least they were mostly at my back instead of in my face. Made excellent time with this conjoined help of wind plus current, despite the fact that I’m absolutely exhausted. I could not stop yawning this morning, and I’m just not getting the rest I need need to recover from the exertions of the day. At this point I’ve been going for 12 days steady without a day off and it’s beginning to catch up with me.

Day 13, July 6th

You know the black flies and mosquitoes are bad when it seems entirely reasonable to drink water through the mesh of your bug shirt.

Large rivers can produce up to 1 billion (that’s with a “b”) adult blackflies, per kilometer of river, per day during peak season, and now is peak season up here. Bug spray and stoicism only go so far. Eventually, there’s no solution except to net up.

This is at the top of the infamous “Portage Rapids”. It starts out big and then just gets bigger and bigger as it goes down, culminating in a series of giant ledges, holes and exploding curling waves.

Every historical traveler, who has travelled this route mentioned these mile-long rapids. Farley Mowat describe them as, “a flume built by colossi” (which is true) and then he says he ran them in an 18 foot canoe outfitted with a 5 hp motor (which is almost certainly a lie).

Historical travelers and the map also describe this rapid having two channels, a left, and a right channel around an island. This is no longer true; all the water just goes to the right. This is a good example of how rivers change over time.

I ran the first two sections at the top, very conservatively, hugging the shore on the left, and never going past the last eddy. A few times I had to get out and drag the boat back up stream in order to get enough distance to cut around a small ledge before coming back into shore. Then I portaged around the very worst part of Portage Rapids and ran the outflow. This maneuver made it a 250 foot portage instead of a 1 mile portage across very uneven to rain. Even these so-called easier sections were quite difficult, and I’m glad my boat is good in big waves, and that I am comfortable with bracing and punching through small holes and curling waves, skills that have been developed in relative safety on the rivers down south.

Seals live in saltwater, and this seal lives most of the year down in Hudson Bay. But apparently he decided to swim 250 km upriver against very strong currents, and super powerful rapids to get somewhere where there are plentiful fish to get fat on in preparation for the long arctic winter. I have seen them before on other rivers going into Hudson Bay, but never this far away from the saltwater.

Yes, there are a lot of bugs in this country; they are the great gatekeeper of the north. But the perfusion of insects also means a profusion of flowers. Everywhere you look there are flowers of all colors, and many of those plants will produce and abundance of berries in a month or so. This photo is the fruiting flower stalk of a tiny willow; the willow is no more than a couple inches high, but it produces these ridiculous-looking bright red flowers that break open to release the seeds.

Setting up the tent, it was difficult to tell the sound of impact on my raingear was raindrops or black flies. It turned out that there were plenty of both, and I had no desire to cook a meal and try and eat it under these conditions. Instead, I just had a few more day snacks, and then retreated to the inside of the tent. My general rule is that if I am not paddling, I should be lying horizontal to recover from paddling.

Today was supposed to be a half-day but in the end, I paddled from 8:30 AM to 7 PM. The motor for my canoe – ie me – desperately need some repairs and refurbishment time. But although it was raining on and off, and although I was wet from the waist down for most of the day, the wind was behind me, and that meant that if I just stayed on the water I would move a little further towards towards my goal. Also, the reality is that I could easily be windbound or stormbound for 3 to 5 days, so even if I’m tired, but the conditions are good I should push it.

Day 14, July 7

You might think that using a compass on a river is redundant, but the rivers up here are not like the rivers down south. They are much newer, having only emerged out from under the ice of the Wisconsin glaciation about 8000 years ago, and they have not had as much time to rationalize and carve more predictable channels. Also, they are on a Canadian shield substrate, meaning that they often do weird things like break up into sections with 1 million islands or turn back 270° from the direction it was previously flowing. Navigation up here is a continuous challenge.

The wind was very strong today, mostly coming from behind, but also sometimes my most stubborn enemy. This section was particularly bad. The GPS promised that there were two routes from a wide and rocky section of river down to Edehon Lake. I picked the eastern route and I picked wrong. The 1:250,000 map swears it exists, the GPS swears it exist, but even with these historically high water levels, there was absolutely nothing resembling a channel in that bay. To get to the other channel – the western channel – and the only one with flowing water, required two hours of backtracking, using a combination of back-exploding difficult paddling, and wading along shallow lakeshore when the wind was too strong to paddle against. Fun times.

Long day! At precisely 6:29 PM the wind dropped by about 2/3 and the bugs came out to find me even hundreds of feet away from shore. I had just entered Edehon Lake, which is a large lake about 20 miles long that I have been worried about from the beginning of this trip. It would be so easy to get windbound here because even a moderate wind can build up very large waves when it is blowing over that kind of distance. Anyhow, the wind conditions were just perfect, so I decided to plow on and make the most of it. I paddled through the sunset, and finally started making camp at 11 PM. I spent 14 hours on the water paddling today. Hopefully the wind conditions tomorrow allow me to complete the lake safely.

Day 15, July 8

What’s going on here? Aren’t you supposed to cook over a fire not beside it?

On this trip I am not cooking over a fire because it is too hard to find sufficient quantities of wood. Typically all I can find are broken willow branches by the riverside, smashed by the ice in the spring. So I am cooking over a white gas MSR stove, and since I am having only one hot meal a day, it doesn’t take very much fuel.

The problem is black flies, so many black flies. There are definitely times when there are at least 1000 on my body, crawling all over the clothing looking for a way in to bite me. I paddled almost the whole day wearing a bug shirt, but you can’t eat through a bug shirt. Therefore, I resorted to lighting a small, willow branch fire, and then hunkering down in the smoke to eat. This gives me a mostly insect free environment to wolf down my food. Funny, I’ve spent most of my career as a firefighter wearing a Self Contained Breathing Apparatus around fired to avoid breathing smoke, and now I’m running right for it.

Even though there are no trees to break the wind here, my Hilleberg Keron 3 is so stable. If there is a better tent for the tundra, then I do not know about it.

The previous part of the river weaves between the open tundra, and the land of little sticks, that transition zone north of the true forest where tiny trees occur in stunted patches anywhere that is protected enough from the wind for the larch and spruce to grow. But now the river starts heading north again, out into the open tundra and trees will become much less frequent.

Today was a good day, despite being very fatigued from yesterday’s push; I managed to make it to the end of Edehon Lake and down the river a little bit.

The PakCanoe is built a little bit like a tradition canoe, kayak or umiak, with a skin stretched over an internal framework. In traditional boats, this might have been a birchbark or animal hide skin stretched over a wooden frame, in this case it is a tough vinyl rubber over an aluminum aircraft frame. This construction creates some intrinsic flex in the boat which has its advantages and disadvantages. It’s great at riding through the big waves in white water where the flex and bend allows it to stay quite a bit drier than a more typical canoe. The bad news is that this flex makes for much slower progress. If having a skin stretched over a flexible frame was faster then every America’s Cup sailboat, rowing scull, and Olympic C1 canoe would be built that way.

Day 16, July 9th

Except for a few blissful times when the wind was very very strong I paddled in a bug net all day long to ward off the blizzard of blackflies that followed me everywhere I went. And in the afternoon when a few rain squalls came through I simply wore the raincoat over the lifejacket over the bug net over my clothing. I did a poll of everyone within 100 miles and nobody objected to this fashion choice.

I was looking for a place to camp and was evaluating the different kinds of tundra and the hummockyness of the terrain when a rainbow illuminated this beach. You don’t get a much stronger sign than that that you need to camp somewhere. There are some old grizzly bear prints on this beach, so I took extra care and running a very clean kitchen and setting up the bear alarm tonight.

Nunavut can be incredibly beautiful, and the extended low angle sun during the summer can lead to a golden hour that are more like a golden evening. Despite all the winds, bugs, and physical hardships, I am incredibly grateful to be here.

Day 17, July 10th

Windbound on the Thlewiaza. I have been battling the wind for over two weeks now, but today it got the better of me. I woke up to a tent that was quivering, and the sound of waves lashing the shore; it was clear there would be no travel until the wind died down so I rolled over and went to sleep again. Later in the day, I added about 400 pounds of rocks and used every single attachment point to hold the tent stable.

It’s a little bit frustrating because the wind is blowing in exactly the right way, just too strong to be out on the water safely. There are lots of rapids coming up and they are difficult enough to navigate without the wind trying to push you into some hydraulic or up against a boulder sieve. I shall have the first hot lunch of the entire trip, then an early dinner, in hopes that the wind calms down by evening and allows a bit of forward progress.

There are two main paddles that are getting me down the river. They serve very different functions.

First, there is a lightweight, carbon fiber, bent shaft ZRE racing paddle with a slightly beefed up shaft to handle the strain expedition paddling. The bend between the blade and the shaft makes your stroke more efficient, meaning that you’re pushing water backwards rather than lifting the lake up. These kind of paddles take a bit of adjusting to, but once you’ve tried them, you never want to go back This is a deepwater paddle, and would not do well with rock bashing, but given that I am taking tens of thousands of strokes a day having a paddle that feels like a handful of air is a huge bonus.

Then there is a heavy duty, carbon fiber, T handle, spoon blade, Werner paddle for whitewater. This is the same paddle I use in my playboat on the local rivers at home so it feels very familiar in my hands. You absolutely do not want your paddle breaking when you’re navigating difficult rapid, which is why I picked something bombproof. It has never failed me, even when I have used it to pole off the bottom of the river and fend off rocks.

You can buy budget paddles for tootling around the lake close to home; they won’t feel good in the hand but they will do the job. But when you are far away from help and paddling for 9 to 12 hours a day, then it’s worth investing in the best.

Day 18, July 11th

I got up at 4:15 AM to try and take advantage of the early morning lull before the wind. I was greeted by this rainbow when I finally set out shortly after 5 AM. Must mean that this was the right decision.

The closer I get to the Hudson Bay Coast the more bearanoid I become. Not only are there still tundra grizzlies in this part of the world there is now a very real chance of running into polar bears as well. I mean, I’m seeing lots of seals, the main source of food for polar bears. The fact that Wikipedia describes these animals as hypercarnivorous, that they are the size of the kitchen table with an incredibly bad attitude does not put my mind at ease.

There is a chance that I will have a pick up on the coast tomorrow. To try to make that work with the high tide. I have to get up early, really early, 3 AM early. and then paddle for all I’m worth. I can do 60-70 km in a slow boat before noon, right?

Day 19, July 12

I absolutely had to meet my pickup boat on Hudson Bay today, so I got up at 3 AM and was on the water paddling by 4 AM. From then until 2 PM it was head down, paddling, stopping every 30 minutes to have some water or some food to fuel the machine.

Over the next 60 km there were many tough rapids and the first caribou of the trip. Finally, I got to the designated pick up point: a shack on the coast that had been abandoned many years ago…

I waited at the cabin for two hours, my contact did not show up and we just could not establish satellite communication through our Garmin InReach devices. I spent hours staring out at the water and saw nothing; this was worrying because the Hudson Bay coast is polar bear central, and no one in his right mind, would spend the night on that coast in a tent or in a cabin without walls…

After hours of trying, I finally managed to get in touch with my contact; turns out that our two Garmin units couldn’t talk to each other for some reason but they could both connect to a mutual friend. So through this system of broken telephone I learned that the water levels had been too low for them to come inshore and they had been anchored 5 km offshore (the Hudson Bay tidal flats are HUGE) for hours waiting for me.

My instructions were “paddle straight out from the river mouth, far from land.” I won’t lie – these are the most worrying travel instructions I have ever received, especially given that bad weather was rapidly coming in from the South. To make problems worse, there are thousands of giant boulders out in the intertidal and a boat looks just like a giant boulder.

After several hours of paddling around in the current among the boulders and both of us firing off our guns to signal each other I found where they were anchored. The flotilla of giant icebergs floating around Hudson Bay just made the whole situation more surreal. But ultimately, I’ve never been so happy to spot a boat in my life!

Safe in Arviat! Thanks so much to Daniel and Daniel, the two Inuit who stoically sat in their boat waiting for the crazy Kabloona in his giant red canoe and then took him for a 2 hour boat ride at 40 miles an hour across an iceberg-littered ocean to get him to town.

Thank you to everyone who directly and indirectly supported this trip. Even a solo trip usually has a giant cast of characters in the background who facilitated, enabled, and helped out. Even solo trips aren’t truly done alone.

If you’ve enjoyed this story, please consider check out my new book Perseverance, Life and Death in the Subarctic!

Perseverance, Life and Death in the Subarctic, is the story of my 42-day solo expedition across the Canadian Subarctic after coming back from the brink of death. On this trip, I encountered bears, storms, forest fires, and raging rapids, and had to find new ways to unlock new levels of endurance and tenacity.

I’ve been told it’s a great adventure story, has lots of useful tips and tricks for the outdoors, and is an inspiring read as well. I’d be honoured if you check it out at the bookstore of your choice or at the links below…