It was a warm June day, and I was in the hospital.

The gurney rumbled through the holding area on its way to the operating theatre. The IV bag swayed above me, and all around, other patients prepared for their own imminent surgeries. Two large doors swung open, and we wheeled into the surgery. Masked doctors and nurses prepared their trays of scalpels as I was transferred to the operating slab.

I shivered, partially from anticipation but also from the cold air that kept the surgeons comfortable under the hot operating lights. I would be unconscious soon, and the air temperature would be a moot point.

A red nylon bag containing my brother’s kidney was on a small metal table off to the side of the room. It had been cut from his body just minutes ago, leaving his orbit to enter mine. Never in a thousand years could I have imagined our journeys would intersect like this. That red bag filled me with both guilt and gratitude. Would he be okay? How could I repay this priceless gift?

Polycystic kidney disease had been killing me for years, inexorably eroding my kidney function down toward zero. The drop from 50 percent to 25 percent function hadn’t been so bad; that drop had been gradual, and my body had had time to adapt. But the descent from 25 percent down to my current 12 percent function had been rough; short walks now left me winded, the sledgehammer fatigue was relentless, muscle cramps came out of nowhere, and mental fog made it harder and harder to think straight.

The walls were closing in. Losing my ability to do normal physical things was panic-inducing, and my quality of life fell off a cliff. I didn’t know the way forward, but it gave me hope that I wasn’t the first to go through this; if others had survived and overcome this, so could I.

The phone call came a hair’s breadth before end-stage kidney failure and mandatory dialysis; my brother’s tests had come in, we were a match, and it was time for a transplant.

The odds said I would probably survive the surgery, but the real question was how much normalcy would be regained afterward. I didn’t know if I could ever return to my job as a firefighter, play with my kids, or do jiu-jitsu. And I was worried I’d be housebound and that my days of roaming far and free might be over for good.

On the brink of the knife, I felt strangely detached from the outcome. I had done everything possible to prepare, and the end of the story was now outside my control. Call it fatalism, resignation, or predestination, but at that moment, it helped to think of the dice as having already been cast. There was nothing left to do, and the outcome was now in the hands of the surgeons and the Fates. If I awoke, then I would learn the results. And if I died on the slab, then the blackness of general anesthetic would merge seamlessly into the oblivion of death. Que será, será.

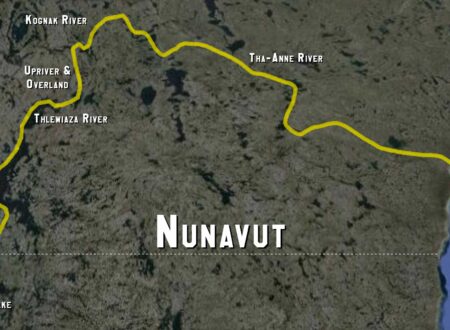

In the final minutes before the operation, my mind wandered unbidden to the lakes and woods of the remote Canadian North. I had had some of my most formative experiences in that landscape, but it had retreated beyond my grasp these last few years as my life had become a blur of doctor’s appointments and medical interventions. “Maybe a successful surgery would allow me to get back up there,” I thought. At the edge of a procedure that I might not resurface from, the North had emerged as a mirage I was reaching toward.

Then the anesthesiologist put a smooth silicone mask on my face and told me to count down backward from one hundred. I didn’t make it very far before the world went dark…

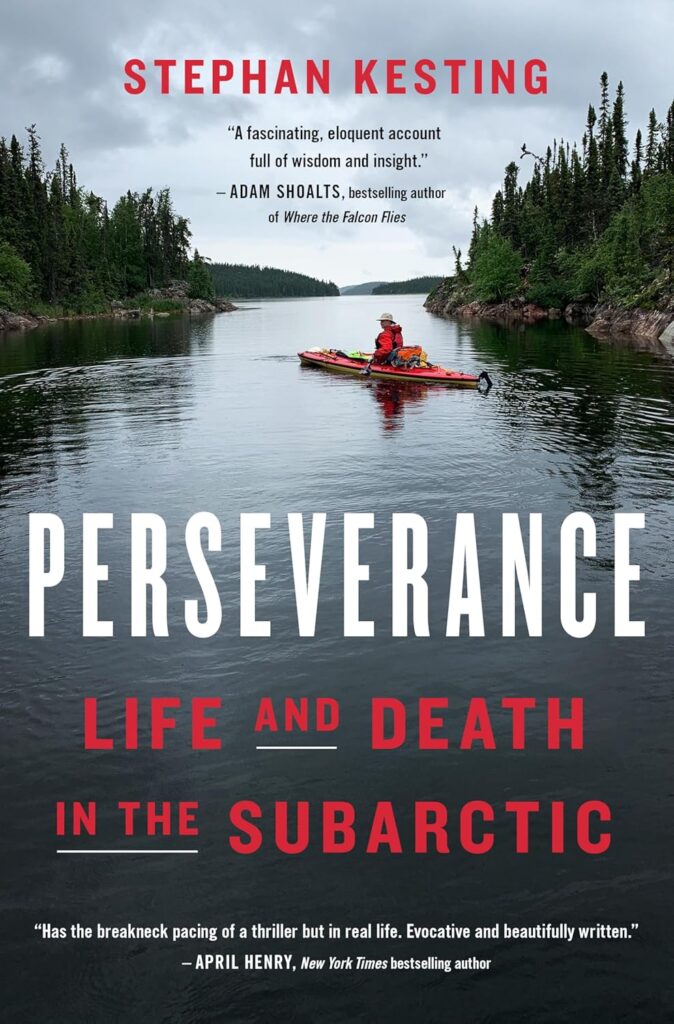

Check out the rest of the story in Perseverance, Life and Death in the Subarctic, distributed by Simon and Schuster and available at Amazon, Barnes and Noble, and Indigo.